At 2 AM, the Slack alert came through. A workflow had failed in production, and we were digging through logs trying to understand why. As one engineer put it, “We don’t have debuggers in this realm. We can’t step through execution. We can’t inspect state at critical points. We can’t see the full picture.”

Debugging felt like archaeology: digging through layers hoping to find clues. Hours later, we’d found the issue. The pattern repeated. Every failure investigation consumed hours of engineering time. Every production issue required manual log tracing. The system wasn’t built for that level of introspection.

If you’ve spent late nights debugging production issues with limited observability, you know the frustration. In hindsight, that incident was an early signal in our product to platform transformation. Our architecture wasn’t built for the kind of extensibility we needed.

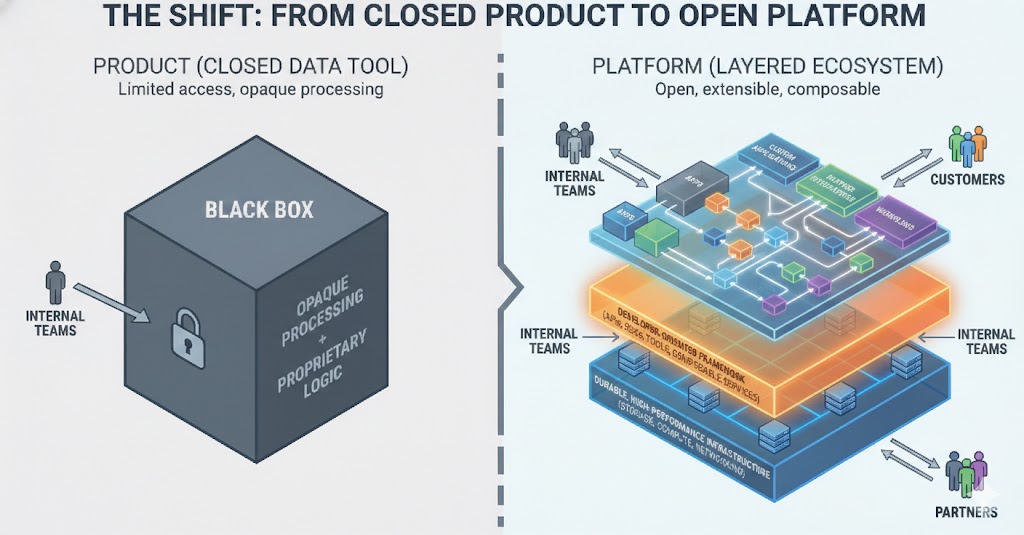

That night wasn’t unique. It marked the moment we admitted our architecture wasn’t just hard to debug—it structurally limited how Atlan could grow. We needed a way to extend Atlan quickly without repeatedly rebuilding the same foundational components—APIs, infrastructure, UI patterns, security, and deployment pipelines—every time we introduced a new feature or integration. But every extension still required heavy internal engineering effort and was tightly coupled to the core product.

This post begins our product to platform transformation by exploring why we needed to rebuild. We’ll cover the architectural constraints we faced and how platform economics made a patch insufficient. The next posts will dive into the technical decisions and architecture that make Atlan’s Apps Framework possible.

What Broke with Our Architecture

Our workflow orchestration followed a Kubernetes-native, infrastructure-coupled pattern that worked well for internal use cases. But as soon as we needed platform-level extensibility, the seams showed: workflows weren’t something partners or customers could safely run and operate on their own. To run a workflow, you had to deploy into our Kubernetes cluster — and we couldn’t hand external builders the keys to our infrastructure. There was no clear “execution boundary” that let external builders bring their own logic while still giving us the isolation, governance, and operability we needed. As a result, most extensions still flowed through Atlan engineering for deployment, operations, and iteration.

The system wasn’t designed for platform-level extensibility. We weren’t just orchestrating workflows anymore. Partners and customers needed to build on top of Atlan—and that required multi-tenant isolation and observability that went beyond what our tightly-coupled approach could provide. That platform architecture—built around a single orchestration path directly tied to our infrastructure—couldn’t support that vision.

As Atlan grew and more customers came in, the pressure was clear: more customization was needed, expectations for performance were higher, and we needed to scale beyond the frontiers of traditional connectors.

The Observability Gap

When workflows failed, we had no visibility into execution state. We couldn’t set breakpoints. We couldn’t replay failed executions. We couldn’t inspect intermediate results. Debugging wasn’t just “missing logs”—it was missing the state and context we needed to reason about long-running executions.

In a team discussion, a platform engineer suggested adding more logging. But the engineering lead was direct: “More logs won’t help if we can’t see the execution state. We’re debugging blind.”

Every production issue became a forensic investigation, consuming hours we could have spent building features—and it also made the system harder to understand and build on over time.

Platform Pattern: Long-running workflows need more than logs—they need introspectable state. Design for observability from day one, not as an afterthought.

The Extensibility Problem

The bigger issue emerged when a partner wanted to build an integration. The question wasn’t whether they had the skills—it was whether our architecture gave them a safe, self-serve way to build and run it. In a meeting with the partner team, the question came up: “Can they build this themselves?”

The answer was clear: “Not with our current architecture. They’d need access to our Kubernetes cluster, our infrastructure, our deployment pipeline. That’s not happening.”

The product lead asked: “What if we just give them more APIs?” The engineering lead’s response was sobering: “APIs aren’t enough. They need to deploy workflows. They need to extend our system. Our architecture doesn’t allow that.”

Concretely, there was no self-serve path for partners or customers to take an idea and ship it end-to-end. Most extensions still depended on Atlan engineering bandwidth across infrastructure, security, deployment pipelines, and shared UI patterns.

Every extension required Atlan engineering bandwidth. Internal teams waited for platform support. Partners waited for custom integrations. Customers waited for features we couldn’t scale to build.

Platform Pattern: If external builders need access to your infrastructure to extend your platform, you don’t have extensibility—you have a deployment bottleneck. You need a clear execution boundary for safe, self-serve building.

The AI-Native Shift

Then came the AI-native shift. Companies are spending less on SaaS budgets and more on AI budgets. In a product planning session, the product lead raised the question: “How do we support AI copilots? They need programmatic access to metadata, the ability to trigger workflows, and extensible interfaces.”

A platform engineer responded: “Our existing system? It’s tightly coupled to our infrastructure and not designed for external integration. AI needs event-driven architecture and extensible workflows. We can’t just add APIs—we need a foundation that supports this.”

To support that shift, we needed a foundation that could connect Atlan to the outside world—including AI systems—without requiring every new capability to be built and shipped inside the core product.

Platform Pattern: APIs expose data and functionality, but platforms also need to expose change. Event-driven foundations let external systems react instead of polling.

Why Extensibility Matters

We tried to fix it incrementally: better debugging, more APIs, better documentation. But as the engineering lead put it: “We’re putting band-aids on architectural constraints. This isn’t going to scale.”

Not all “platform extensibility” is the same. There’s a spectrum of how deeply external builders can participate:

The Extensibility Hierarchy

1. APIs alone: Partners integrate with you. They can read and write data, but the logic still runs inside your systems.

2. APIs + some extensibility: Partners can integrate more deeply and react to changes, but they still depend on you to deploy and operate their extensions.

3. APIs + a self-serve execution model: Partners build on you. They can ship workflows and integrations without needing access to your infrastructure or deployment pipelines.

For external builders, we were effectively at level 1, and we needed level 3. The gap wasn’t something we could bridge with better documentation or more endpoints.

Extensibility defines who wins long-term in the software platform space. A single company cannot build every workflow, integration, or specialization customers need. Without a framework, the platform becomes rigid and slow. Customers outgrow it. Customers and partners innovate outside the platform, not on it.

In an architecture review, we realized the math was clear: products follow linear growth—ten engineers build ten features, a hundred engineers build a hundred features. But platforms are different. Ten engineers can enable a hundred developers to build a thousand features. The math compounds. The innovation accelerates.

The numbers told the story: Salesforce has 3,000+ apps in AppExchange. Snowflake has an Apps Marketplace. Slack has 2,000+ integrations. Shopify has 8,000+ apps. They didn’t build all those features themselves. They enabled others to build. That’s the power of product to platform transformation.

What This Unlocks: From Product to Platform

The introduction of an extensible Apps Framework will fundamentally shift Atlan’s trajectory: from a company that individually delivers features, to a platform that enables a global ecosystem to innovate independently.

By allowing internal teams, solution engineers, partners, and eventually customers to build apps on a shared foundation, Atlan can create an ecosystem similar to Salesforce, Slack, or Shopify. New capabilities will no longer depend solely on Atlan’s core engineering bandwidth.

This also enables marketplace dynamics beyond traditional connectors: apps, automation, compliance packs, and AI-driven assistants. And because apps are decoupled from the core, teams can ship faster and experiment with lower regression risk.

The long-term payoff of a platform is community—once others can build, innovation starts to outpace what any single team can plan for.

The long-term payoff of a platform is not features—it’s community. This will unlock hackathons and developer events, certification programs, partner-led industry solutions, and crowd-driven innovation at scale. At that point, growth becomes asymmetrical. Innovation happens faster than we can plan for it.

We Decided to Rebuild, Not Patch

Rebuilding meant solving a challenging equation. In a design review, the engineering lead asked: “How do you make something more flexible AND faster, cheaper, scalable, and secure?” For us, it wasn’t a trade-off discussion. We needed everything at once. The older system had no way partners or developers could come and build on top of the Atlan platform. The existing systems were closed, hard to debug, and less scalable. We had to figure out and rework the entire systems from scratch to make them more open, integrable, and scalable, all while ensuring the new systems are performance-oriented and cost-optimized.

This wasn’t just a technical build. It was a design of architecture, incentives, governance, and ecosystem strategy.

In a final architecture discussion, we realized these weren’t bugs we could fix incrementally. They were foundational limitations that required a redesign.

Rebuilding meant accepting months of work before users saw value. It meant betting that we were right about platform economics. It meant owning the consequences if we weren’t. If you’ve made a similar decision, you know the weight of that moment: the risk, the cost, the uncertainty.

We shifted from fixing symptoms to designing a foundation others could build on.

Building the Foundation Others Will Build On

In the first architecture planning session, a platform engineer said: “This isn’t feature development. This is platform engineering at strategic scale.” The architecture lead added: “It’s like building AWS itself, on top of which the world will build.”

This meant solving distributed systems challenges: durable execution for long-running workflows, event-driven architecture for real-time reactions, microservice isolation for security and scalability. Platform design adds another layer: security at every boundary, multi-tenancy with proper isolation, scalability that supports hundreds of apps, resource management that balances performance and cost.

Building platforms means you can’t leave any stone unturned. End users will use every feature of the platform. They’ll come up with use cases we haven’t even thought of. The work required collaboration across Security, Platform, Support, UI, Documentation, and external partners. This is ecosystem work.

Product to Platform Transformation: Key Takeaways

- Architectural constraints limit platform extensibility. Our previous architecture worked well for internal use cases but lacked the observability and extensibility required for platform-level building. When every extension requires internal engineering bandwidth, velocity slows—and partners and customers can’t build on the platform in a scalable way.

- Moving from product to platform unlocks compound innovation. The math is compelling: products follow linear growth, while platforms enable compound innovation. Ten engineers can enable a hundred developers to build a thousand features. This platform shift is what separates products from platforms.

- Platform engineering requires foundational infrastructure. By building systems that support multi-tenant isolation, secure app deployment, event-driven architecture, and marketplace dynamics, we enable the kind of ecosystem growth that powers modern platforms.

- Platform engineering is ecosystem work. Platform transformation requires cross-functional collaboration—across Security, Platform, Support, UI, Documentation, and external partners. Success depends on aligning architecture, incentives, governance, and ecosystem strategy from the start.

From that 2 AM debugging session to the daily “Can you build this?” questions, the constraints were clear. Now came the hard part: figuring out how to solve them.

In the next post, we’ll dive into the technical decisions behind Atlan’s Apps Framework: how we designed for execution-state visibility, multi-tenant isolation, and event-driven integration—the gaps we couldn’t bridge with more APIs, more logging, or better documentation.